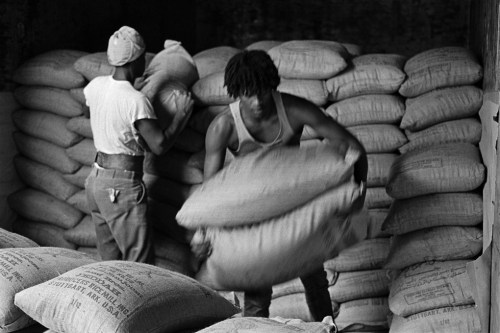

Keith Calhoun

Dock Worker Throwing 100 lb. Coffee Sacks, 1982

Photo courtesy of Antigravity Magazine

Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick’s latest exhibition “Labor Studies” is on view at The Contemporary Arts Center of New Orleans through February 10. Their book, Louisiana Medley: Photographs by Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick, is available through The Frist Center for the Visual Arts. For more information, visitcalhounmccormick.com.

In 1978, Chandra McCormick, a young woman looking to have her portrait taken, sought out Keith Calhoun, an up-and-coming photographer. Both children of working class parents and natives of the Lower Ninth Ward, they got along well enough. So Keith invited Chandra to see how his pictures were made—“She kept brushing up on me in that darkroom,” said Keith, who has no shortage of anecdotes—and serendipity ensued. Chandra was captivated by the process. And Keith, the lone artist, was suddenly in a partnership. Chandra began assisting Keith with developing prints, quickly learning the craft. Her aptitude for image-making was self-evident, and it wasn’t long before she and Keith were photographing side-by-side. At present, the couple—longtime husband and wife—are two of the city’s foremost contemporary artists, documenting Black experiences in the South with unprecedented perception and ardor as a part of an artistic collaboration spanning 40 years.

Some of the pair’s earliest photography can be traced back to New Orleans’ shipping wharfs, recalling a bygone era along the Mississippi River of 100-pound sacks of coffee and flour being lifted and hauled by Black men. In 1980, the couple began photographing inside the country’s largest maximum security prison, Angola Penitentiary, their initial access facilitated by Bernard Hermann, a white photographer from France. Along River Road, the artists have spent decades documenting fieldworkers on sugarcane plantations, amassing a collection of images encapsulating an overlooked and vanishing form of labor. Through all this, Calhoun and McCormick have fastidiously photographed Black New Orleans life and culture, their work serving as a vital record of the city’s history told from the perspective of those responsible for shaping it.

Following Hurricane Katrina, Calhoun and McCormick returned to their flood-ravaged home in the Lower Ninth Ward to find much of their life’s work underwater. They salvaged photographic negatives floating in stormwater, stuffing the damaged goods in trash bags placed inside of a freezer for safekeeping. Eventually, they returned to these tarnished negatives, creating a powerful series of prints marked by a life-altering event. And of course, Calhoun and McCormick have never stopped shooting. Throughout their lives as photographers, they’ve committed themselves to the documentation of Black life and labor. Their familiarity with their subjects affords their photographs the rare type of clarity only found in the perspectives of insiders. As time goes by and more and more of what Calhoun and McCormick document disappears, their expansive body of work will only continue to grow in importance.

The following interview took place in Calhoun and McCormick’s Lower Ninth Ward home studio where we discussed their lives and work, surrounded by their photographs.

Would you be willing to explain the evolution of your partnership? I know the origin story of Chandra seeking out Keith for a portrait in 1978, but how have you both managed to maintain such a long lasting artistic relationship?

Chandra McCormick: So you already know the story of how I became fascinated by photography, and how I developed my eye through printing. When Keith saw my potential and encouraged me to shoot, that in itself opened up my world. Even though we shoot the same subjects, we see things differently. I think that our longevity comes from that partnership, also through learning. I learned a lot of shortcuts with him teaching me things that took him years to learn. He taught me about looking at the frame, making sure what I saw was what I want. Being together in the dark room and working together on projects, I think that helped too. And knowing that, you know, we struggled through this together. It’s been a commitment to each other as well as a commitment to what we’re doing. It wasn’t an easy road because photography is very expensive and it’s hard.

Keith Calhoun: Once you develop a passion for something, you can’t put a money value to it. What we do, it comes from the heart. I always knew it was necessary to become keepers of our culture. And it’s a sacrifice, this habit of film. Some people have different habits, but ours is film. And we was never able to get grants or get a job at the Picayune. I applied a few times, but they wasn’t always open to African-American photographers. [African-Americans] have a strong presence, even now. You see many of us participating in the culture, but very few of us are documenting our own culture. Chandra, she brought a lot to the table because as she started to learn to print, she’d see a lot of my mistakes and she would learn from them. So when she started shooting, she already was frame-conscious. All I had to do was help her develop her eye, the seeing. That’s what photography is, the seeing. She would learn each lens, master each one. So we was honored to be able to come together and share the same passion, and we struggled together for many years, and we’re still in the struggle. But we was fortunate to have the vision to go out and document parts of the community that have vanished. Like shooting the docks in the 70s. I think I was like 19 years old. My father, he was a dock worker, same as most of the men in the neighborhood. So all my life I was around workers, union men, men who stressed that you ain’t going to get nothing laying around in bed. You got to get up and get it. In this city at that time, my father could walk from Delery Street to the river. We had a community of men who came primarily from sharecropping in the backcountry to New Orleans. It was hard on the backroads where these people were coming from, because they still had them on the plantations. So the docks was the big boon here for a lot of people. I’m the product of that, and my father always supported us, our family. My daddy would sometimes buy me a whole brick of film.

Can you tell me more about shooting on the docks?

KC: At that time, not everyone could see the beauty in those men tossing those big bails and sacks, sweating. You know, lifting those big bails made paradise for the wealthy people uptown. Those workers, those were the men who changed the conditions of the riverfront. The river was what kept Back of Town together, that was the lifeforce. If you got a job on the docks, you made more money than a schoolteacher. And with my daddy out there, I was honored to have that insight of the docks. When I went out there, it wasn’t like I was a stranger. People would say, “Oh, that’s Calhoun’s boy.” They had another photographer out there, he was a Frenchman named Bernard Hermann. He would have his bandana on and we’d be riding our bikes along the wharf. They thought we were some type of government men ‘cause at that time there were so many drugs, Carlos Marcello and them was running those docks. This was the city—so much stealing going on and stuff coming in and we just had a letter from the port that let us shoot anytime. So I’d just go shoot—morning light, evening light. And even customs guys would pull me over and be like, “Who you with!?”

CM: He’d have to show his letter.

KC: So my daddy said, “Whatever you doing, you hurry up because you going to find yourself thrown in that damn river. You got them white folks in the office wanting to know what’s going on, this guy going up and down the river.” At that time you could ride all the way from Poland to Nashville. So for me, as a photographer, you had all these men, hundreds of of men working, all this great lighting coming in through the walls. But not everyone saw it like that, they didn’t see the beauty. When Chandra was printing those, she would say, “You need to get in closer.” And that’s when I messed up and told her she should shoot. And we was fortunate, because Chandra, she spent one year working with a framer, just to learn how to frame and mat our pictures for presentation. I couldn’t have found nobody better to have the same interest. Through sacrifice, in the end, we was able to build an archive of life in New Orleans. And we still have Kodachrome we never got printed. Even like 40 years back, we would just shoot, process the film, and we wouldn’t even get it printed. We’re still just now digesting a lot of our work.

CM: Some of our cohorts, they’d say, “Y’all are antiquated. Y’all are dinosaurs. People want their pictures immediately, and y’all got to do all of this and that. Just shoot some color film.” But we shot slides because it was more permanent and archival, and they’ve held up.

How did you decide when to shoot color and when to shoot black and white?

CM: I love black and white because to me it’s more dramatic. I like the tonal ranges—the blacks, the grays, the whites. In the beginning, we shot color every now and then, but publications would call us and sometimes in the beginning they weren’t interested in black and white, they wanted color.

KC: I like seeing the early morning light hitting the cane in a color slide, and I liked the black and white. So we were able to use two different [camera] bodies, which was pretty costly, but it was worth it in the end.

And are y’all shooting digital?

CM: We shoot digital now, but we also still shoot film.

KC: With the digital, you overshoot. It’s overkill, because you can just constantly shoot. With the film, you have to put more time into it. You’ve only got so many frames.

CM: You’ve got to make it count.

KC: As technology changes, you got to question it. I find myself with all these hard drives, and now you got to back this one up to this one, and it never stops. In 50 years, with this Louisiana humidity, the hard drive, what’s it going to look like? With a negative, I can go and process a roll in 30 minutes knowing that that negative is going to stay around for at least a hundred years.

“You don’t sneak a picture. It’s not going to be the real thing, and it’ll be much better if you let that person know who you are and what you’re doing.”

I wanted to hear about your relationship with [late New Orleans photographer] Harold Baquet.

KC: Harold was the best. He was one of my kid’s godfathers for many years.

CM: Both our kids.

KC: No matter what, he bought those kids something every year. Rain or shine, he was there always. Harold used to be [then New Orleans mayor] Dutch Morial’s photographer, and he knew that the new administration wasn’t going to keep him, so he came and said, “Look, you got a baby now. Go talk to the new press secretary.” And that’s how I was able to get the job being a photographer for [succeeding mayor] Sidney Barthelemy. I was able to chronicle a lot being a city photographer; that gave me a lot of leverage. And then me and Chandra, we was the school board photographers. That helped a lot, too.

CM: And Harold was an all around dude. He could do anything. He was a licensed electrician by trade. He was really good with electronics, and he was a self-taught photographer.

KC: And he worked with us teaching the kids. We would go to the projects and bring cameras, and we was always bringing them film and processing it, teaching them the value of documenting neighborhoods. It was great to have someone like Harold. He was a brother to us.

CM: Our outreach program, it was called Project Focus at the time, we reached out to all the projects in the city. We had St. Bernard Project, Desire, Fischer, Lafitte, Florida. Uptown, too, the Melpomene, Calliope, St. Thomas.

KC: And then we had kids from the Covenant House, too.

CM: After our work with the kids in the projects, Covenant House reached out to us. So then we began to work with the homeless kids as well.

And a lot of those neighborhoods you mentioned have been broken up now.

KC: Gentrification.

CM: Well, the families are sparse.

KC: They’re so displaced now.

CM: A lot of people have moved out because they can’t afford to live in the city.

KC: The city been wanting to take the city back, and Katrina helped them get it back. And now you can go to the second line in Treme, and half of those people aren’t even living here no more. Even though we’ve been displaced and disenfranchised, pushed out of the city, we still gravitate back to that community where it all came from, and that’s one of the great things about our culture. Even the Mardi Gras Indians—some of those guys are living way outside the city now. And the neighborhood bar they used to frequent has changed. It’s no longer part of the community. It’s a different energy now.

Your friend Harold once said Keith “had a knack for finding things that wouldn’t be around much longer.” I was wondering what your thoughts were on that.

KC: We try to document things that are vanishing, forms of labor. Like the sugarcane workers out in the rural parishes. They’re disappearing, because of the technology coming in. The only thing that hasn’t changed too much is Angola.

CM: No machinery. It’s all by hand.

KC: Yeah, you’re hardly going to see any tractors in Angola. But when we go to sugarcane fields now, they’ve got a machine that cuts five rows of cane at a time.

CM: And it not only cuts the cane, it throws it into the gondola and the scraps are left there to burn. They’ve just got two men out there.

How many workers were there before?

CM: It could be anywhere from seven to twelve people in the field, scrapping. Someone on a tractor. Another person on cane cutter… And now it’s two, and they’re just manning the machines.

KC: You don’t need no scrapper no more. So it’s sort of like a lot of people wasn’t able to leave the backroads, wasn’t able to get off these small plantations. They’re kind of stuck behind the backroads right now. There’s no need for their labor. And then a lot of these planters, even though they talk about they don’t want no Mexicans, half of these plantations is all migrant workers. You got these Republican, “Make America Great Again” people who own these plantations, but you can go there and see who’s doing the hard work. They work them from 5:30 in the morning to 7:30 at night.

In your most recent exhibition, “Labor Studies,” you have photographs of New Orleans construction crews, housekeepers, and cooks, displaying images of these workers in a museum setting. I’d like to hear why y’all think it’s important to document these people.

CM: Because they’re the ones who make things happen in this city. They’re the ones who build everything. They serve everybody, but they’re the underserved.

KC: They’re the unsung heroes.

CM: Exactly. We see them everyday, but they’re invisible to most of us.

KC: We documented this one lady who was a presser at a cleaners. But on Sundays she’d be dressed up; she’s the mother of her church. When you see these people’s lives, what they involved with, it’s important to show them. They the backbone of the city. The dock worker who sweated all day, he’s a Masonic brother. At that time, my father and men would get together, and someone would buy a lot and all the men would get together and build a house. The women would cook. Here in the Ninth Ward, where you had more Black homeowners than any other part of the city, that’s how it was built up. A lot of the people we photograph are not the people that you usually see. But in New Orleans, you could be a gardener and have a funeral as big as the governor. You have that benevolence here. For a lot of things, we felt if we don’t document it nobody else would. That’s why we try to encourage kids. We grew up among workers. My mother was a custodian. Chandra’s mother was a seamstress. So we were around working people, we was able to hear their testimonies. Our young kids today are not being taught in the schools about the people in their community. We have to carry that burden—it’s up to us as artists. Our work in the community, it’s a reflection of us but it’s really for the people, because it came from the people. We have a lot of history here. People will come by and say, “Hey man, you remember you went to Mother’s Day at the church? Did you take pictures of my mother or my family?” Because a lot of people lost a lot.

CM: The maid we shot, Carla, she works at the Andrew Jackson Hotel. And it’s people like Carla and other workers, if they weren’t there to do that laundry or make that bed, what would those tourists do? How would that business function?

KC: New Orleans to me is still a banana republic, you know? That’s what I see it as. A lot of people here are mostly servants to the rich. The people doing the dirty work don’t get the respect they deserve. A lot of people overlook those folk. We try to catch them in their dignity.

The work not only focuses on often omitted narratives, it also reframes narratives that are already familiar. You document street musicians, Mardi Gras Indians, and Social Aid and Pleasure Club members, equating the traditions of culture bearers with forms of labor. Can you speak to that?

CM: Our cultural bearers also make this city function. Really, they’re big on helping the city, and I feel that they are often not appreciated as much as they should be. Second lines are something that bring people to the city. They put down all that money on their uniforms, their clothing, and then they’ve got to pay $2,500 for a permit?

KC: But that’s how it’s always been, as far as the passion these people have.

CM: They have commitment. It’s what they love.

KC: They buy the clothes, pay the band. Although some of this is changing because now they have the DJ floats in the parade…

CM: The tradition is changing. You can even look at the bands. When we began photographing the bands, they all wore uniforms. The old men, like Mr. [Milton] Battiste, I remember one day James Andrews showed up out there and he didn’t have his hat. Mr. Battiste said, “Where’s your hat?” And he said, “Oh, I forgot it.” So Mr. Battiste told him, “You better go home and get it, you can’t play without your hat.” They had to have pressed white shirts on, black pants, and their black hat. They had to be traditionally dressed. Even young guys. That’s how the old guys set the standard. I look at the musicians now at the second lines; sometimes they might all have on the t-shirt of the club or the band, but it’s a t-shirt, you know? And sometimes they’re just dressed all kinds of ways. In the beginning, the band was always distinguished. You could see who the band was, you knew who the second liners was, you knew who the club was.

Why do you think that change has occurred?

CM: I think it’s the younger people, and some of the older people who were establishing those rules aren’t here anymore. It’s not carried on.

KC: If you see the Young Tuxedo band, all those old guys continue to keep the tradition. It’s different values now. There’s a lot of stuff changing like that, but the city is changing, too. We go into the Treme now, and it’s just so sterile. There’s not even people sitting on the porches.

CM: I think New Orleans is like that. It’s not just Treme.

KC: And here in the Ninth Ward, do you hear any kids outside anymore? People can’t afford to live in this city no more. The artists and musicians, they can’t afford the city.

CM: We know Indians that have had to move to Slidell, but they still perpetuate the culture.

KC: What used to be grandma’s house is now an Airbnb. A lot of young Blacks don’t have successions in the family. A lot of houses get caught up in tax sales or someone comes in and offers them $100,000 and they take the money because grandma might have bought the house in 1950 when she paid $10,000. But when they split that money up when grandma die, they don’t have anywhere else to go. It sounds like a lot of money, but that same person who bought your grandma’s house done turn around and ask $1500 a month. And you got people coming at you. You can look at these signs: “Cash for your House.”

CM: There’s a sign, you know, it’s strictly for us because no other person can view it [laughs].

Serious?

CM: I’m serious. If you look out this window [moves window curtain to reveal “Cash For Your House” sign tacked to utility pole], it faces directly at us.

KC: And then you got people calling you, and sending postcards, saying “Jesus loves you,” so you know it caters to older Black people. People are being played out of their property. I’m glad we was able to document Bywater and Treme before it all gentrified, because it was full of great moments. People were so open, you could go there and smell someone cooking and people don’t even know you and say, “Come on in and eat.”

How do you navigate between documenting culture and participating in it? Or are they one in the same?

CM: I think that we are participants. We’re documenting, but really we’re on both sides of the lens. We’re a part of the community, we know the people, and sometimes even though we’re shooting we stop and we dance with them too. It’s really hard to hear the music and not move. As Kalamu Ya Salaam said once, “Our music is like pent up piss.” [laughs] You know, you have to move. I remember that phrase because I think it’s poignant.

I’m really curious to hear about how you decide when to shoot and how y’all capture some of these shots. I’m thinking of this one photo [“Cutting The Body Loose”] where a woman is surfing on top of a casket.

CM: There are certain moments in our culture where things happen. As far as funerals, it’s a procession, but it has a rhythm and an energy. Things happen. And when you’re in it, not just photographing it but in it, you get in tune with that rhythm.

KC: You’re keeping with the beat.

CM: When it comes to distinguishing what to shoot, honestly we shoot everything. We try to shoot every moment.

KC: But you have to know the moment—say, when they cutting the body loose. Everybody don’t know they finna cut the body loose. Just through years of documenting, we know. We want to be ready when they cut it. And they got certain people, like Loyce Andrews, them people going to be there that day no matter what the situation is. They the last of the grand marshalls. In that photo, that was her nephew, Trumpet Black. And Loyce, even for her own son, will ride the coffin, she going to go all the way with him. Cutting him loose, it’s like sending him off. That last moment. And that’s a moment you want to capture, her walking him to the gates. She’s one of the best. But we already know to get in position. There’s so many photographers and cellphones—

CM: It’s crazy.

KC: So a lot of people don’t know the moment. Like this photo [points to photograph of second line dancers titled “Ascension”], this is the Furious Five right here. When you see these guys, they rolling. So you got to be moving with ‘em. Now you got these people at the second line [in nerdy white person voice], “Hey buddy! Move out my way!”

CM: But the line is moving!

KC: I’d get in fights, ‘cause you got to push people back and let the procession come. But we so good with it I can shoot with one hand now and just keep hitting, where you got one guy and he out there with his tripod like, “Move! Excuse me!” And it’s like a tourist attraction, and some lady is like, “You think you own the street!” And I’m like, “Lady, you got to keep it moving.” Because I’m constantly moving with the line, and I’m hitting all the way and I’m pushing her back too.

CM: If the line is coming towards you, they’re going to walk right over you if you don’t move. Or the persons that are navigating for them, they’re going to push you out of the way. I been hit with the Indian stick, I been pushed back, I’ve got the, “Get out the damn way!” I just got to respect them and move the hell out of their way because they deserve it. You can’t interfere with the parade.

KC: See, 30 years ago, when we started documenting there was only a few photographers. Jules Kahn, he was an old Jewish man. On any weekend, he might go to three or four funerals. He started photographing in the 1950s. Even his children didn’t really know him. He was a man who owned pretty much the whole French Quarter, but his passion was photography.

CM: He’d call us sometime. We rented from him, one of our first apartments in the French Quarter. And he’d call and be like, “Y’all going to so-and-so’s funeral?”

KC: He was a person that loved the culture. But now, you go to Indian practice you might see Tulane University students photographing Indian practices, which takes away from the culture.

I was wondering what your take was on the perpetual influx of photographers documenting New Orleans.

CM: I think it’s a rape of the culture. I really do. I’ve been told, by an Indian chief, that they have these bars now, where the new people have moved in, they’re not African-Americans, and they have sip and sew parties. I realize it’s a street culture and the streets are public. But I remember a time where no one else entered our community and our culture was very sacred and dear to us. And now I feel it’s been infiltrated; it’s being diluted with other people joining our clubs that are not of our race, our culture. Especially with the Indians and the sewing—it’s like, OK, you can stand on the sides and watch. But how dare you try to participate. And they’re marketing our culture around the whole damn world. I think that’s wrong. It’s like the Indians being on stage during Jazz Fest. It takes it out of context. But they need money.

KC: I think in the beginning, people like Tootie Montana never had to depend on that, because at one time those people did it from their heart. A lot of people, they come here and photograph the Indians, and they exploiting them. And they culture vultures, because they’re taking and they not giving nothing back. They just come and take. An Indian can go to New York, see himself on a big billboard, and meanwhile he’s struggling month-to-month trying to sew a suit. Then all of a sudden the Indians start competing because of commercialization. A lot of them trying to get paid thinking that they going to make all this money from selling the suit, because a few people might come in and offer to buy their costumes. But in the end game they not getting anything.

CM: They do it because they love it, and they’re exploited because of it. The Indians, they’re a neighborhood culture. And I’ve noticed in the last ten or 15 years, a lot of people, so called “academics,” they want to come in and make it something that it’s not. Or they come in and say, “Oh, we need to write about this. We need to write the steps.” You don’t need to do that! If it needs to be done, it needs to be done by the group of culture bearers, not other people.

Also included in the exhibition on labor are portraits of prison inmates in Angola. Can y’all talk about the significance of including those photographs?

CM: As Keith was saying earlier, there’s no machinery there. It’s 18,000 acres. Everything is done by hand. When we talk with Henry James [former Angola prisoner exonerated after 30 years in Angola] he talks about how they got the hoes and they scrape into the ground. When they’re out there working, there’s a rhythm to that, too. You have to be in line, keep moving. The whole line keeps moving and if you miss a spot, there’s one guard who has a horse that kicks up and shows where a person missed. So Henry would work the whole week, then when the weekend came, they’d have off privileges. But the guard would say, “Oh no, you missed a cut on Tuesday.” Labor, that’s all they do there. Angola is self-sufficient. They don’t need anything from the outside.

KC: With Angola, like half of the people that grew up in New Orleans have some family member in the prison. Angola is an enterprise. At one time, you could go to Angola prison, get out, and go work on the docks. You can’t get a job like that no more. But at one time, I remember guys being released from prison and they was able to come work and live a comfortable life. And now, because prison is a big business, Angola has over 6,000 inmates and it’s a whole town of its own, surviving off the inmate population. When you go to Angola, you got 20-to-life. They not taking nobody unless you got a long sentence. The business of prison is meant to keep these guys and the labor is pretty much free because you’re making like 20 cents an hour. You’re not going to get no social security. Our friend Gary Tyler, he did 42 years.

CM: And he was innocent.

KC: And he went to death row at 16. Imagine at 16 years old, they thought he was going to get raped and everything. But the Angola 3 guys protected him, because they couldn’t believe that the state of Louisiana would put a 16-year-old boy in the cells with them. Now we have the private-owned prisons, and they worse than Angola. The towns depend on the beds being filled, and New Orleans is an incubator for the prison system.

Y’all started taking pictures at Angola in 1980. Can you talk about the changes you’ve observed throughout that time?

KC: When I started photographing Angola, they had to make a quota. At one time, a man had to pick a certain quota of cotton every day or else you could be handled bad. They don’t have stuff like that anymore. Much hasn’t changed, though, because every morning the men still have to get up and get in that field. And they don’t get no profit from the field, so imagine you spent 30 years working the field, and there’s no type of real compensation. And then you get old, still in prison, and you’re all wore out. The prison was built upon slavery and free labor, and it wasn’t about rehabilitation—it was about how much the drivers, those men riding horseback, could push you. And if you can’t keep up, you go to the dungeon and lose all your privileges. You in the hole. As far as putting Angola in our work series, we felt that the prison work and the plantation work wasn’t too much different. In fact, some of these women in the free world are catching more hell than the men incarcerated in Angola. They don’t have no more work in these small towns because the small town sheriffs are getting free labor from the jails now. They don’t need the women to work the fields in East Carroll Parish, they can go to the sheriff and get a crew from them. That’s why we focus on the demise of Black labor in the South, because there’s no need for us anymore. The docks is gone; you go to the plantations and there’s migrant workers there. The cotton gin is all automated now. But in Angola, that’s the only place where you see physical work. It’s mandatory that you get to that gate or else you going to be hounded. If you feeling bad you can’t just tell the captain you’re sick. You end up in lockdown.

Can you talk about what the process of building relationships with your subjects looks like?

CM: Even when I first began to work with Keith, his approach was always communication, talking to people, let them know what we’re doing. I learned the same way. You don’t sneak a picture. It’s not going to be the real thing, and it’ll be much better if you let that person know who you are and what you’re doing. Because sometimes, even though you tell people what you’re doing, and they might be at ease, you can talk to them and take their picture and be photographing them until they’re so comfortable with them that it’s like the camera is not there. We try to create a relationship with our subject matter, even if we meet them one day and don’t see them again. We still try to make some type of formal contact with them. To share our work with them.

“It’s important to have a record. To see Black people in honor, the beauty of that.”

Both preservation and loss are recurring themes in your work. Why do y’all think that is?

KC: I feel as a documentary photographer I’m just touching the surface of what needs to be presented. It’s important to have a record. To see Black people in honor, the beauty of that. But what we also show in our work is that much hasn’t changed for us. In a way we’re kind of worse off because at one time we had more land. My daddy bought a lot at 21 years-old, and Black men were coming together and putting their resources together to buy property because we came out of sharecropping where you couldn’t buy the land. We try to preserve what life was like in the Ninth Ward. We probably have the only record of Black churches in this neighborhood. When you go on the north side now, you just see empty lots. But before Katrina we would frequently visit those churches and document. Even though we were documenting, now I see how important it is to have that record. When you pass the cane now, you see the machine. You won’t see Gail Dorsey [pictured above] working no more. And now, you don’t have enough writers—at one point in time you would open up the Sunday Times-Picayune and see a photo spread with a writer who went out and worked on a piece for a month. Now that’s gone. You might catch it on the internet. How we work, we can leave from our house and just go shooting, collecting stories. And we don’t have no grant fund, but the work is still necessary. Anything you have a love for doing, and you can go do it, that’s your wealth right there. Doing the work. It’s nice that we in the museums and galleries, but my people from the community, they not going to go to the CAC [Contemporary Arts Center]. It’s not always community friendly. Like NOMA [New Orleans Museum of Art], some of them museums are like plantations. They collect things and hold them while the donors are descendants of the same people who got us on the backroads. Artists have to engage, being the keepers of our culture, because if we don’t teach our young people the value of what’s around them they’ll never know. And they’ll repeat history. A lot of these kids, they don’t know about Angola until they get there. I love my work being at the CAC, but I would like to see it go to the schools, so the kids can see. I feel even the churches should engage in art. The Black churches have better space right now than any place else in the city. They could take down some of those Jesus pictures and put art up, and they’d become a whole other entity in the community. That’s my own perspective, but we need to have more engagement and community spaces as artists, because a lot of these institutions aren’t so accessible. When I went to school in California and got into art, I worked for a paper called The Red Tide. I didn’t know what a communist newspaper was. I just knew all these middle-class kids had the red book [Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung] all the time and talked about Marx. And I knew they had a badass darkroom! They had this nice setup, complaining about the system, but they lived in Hollywood Hills! And I would go out and shoot the rally with the Black Panthers and got involved with the Watts Writers’ Workshop; they took me under their wing. And I seen what the Black movement did for the arts. I seen how important art is. If kids could find places to get engaged in their community, they won’t have to need to go out and steal, because you giving them something.

CM: And now they’re taking art out of the schools.

KC: So they’re setting these kids up to fail. African-American artists, we have to have a commitment to our community, where we control spaces.

Why do you think it’s taken people so long to come around to your work?

KC: It’s about the power structure of the art world. To me, a lot of the time, even with galleries, most of the African-American artists here are great artists, but they don’t get the support or the recognition. I know some incredible artists in this town—Ron Bechet, Martin Payton…

CM: And they haven’t gotten their due.

KC: Me and Chandra, we fund our work out of our own pocket. But as African-American artists, we’re still at the bottom as far as getting into these institutions.

CM: If we were not African-Americans living in New Orleans, they’d probably be touting our names.

KC: We’re the first artists from Louisiana to go to the Venice Biennale, and you would think the city would embrace that. You would think the Ogden Museum of Southern Art would have our work.

CM: I think it’s racism, honestly. I really do. We can’t let that stop us, though. We continue to work.

KC: I feel like we’ve been blessed, ‘cause we’re still able to document and we’re still in it, you know.

CM: And through all of this, we have never been represented by a gallery. We don’t have a gallery. I’m happy and proud that we’ve accomplished what we have.

KC: You don’t let that discourage you or hold you down. You still have to find the means to create your work.